Author Phil Warburton ◦

Urban development is usually not great for wildlife. However, surprisingly, there are some good-news stories that we can celebrate, and which give cause for optimism.

During the last 100 years, there has been a marked increase in the human population on the south coast of New South Wales and large areas of land were re-zoned for human housing.

When such land was allocated for housing, local and state governments resolved to progress with development whilst mitigating some of the environmental impacts. Accordingly, some areas were deliberately set aside for urban nature reserves.

In many cases, the new housing areas were previously agricultural land that had already suffered environmental damage. One such area was in the Eurobodalla shire south of Moruya.

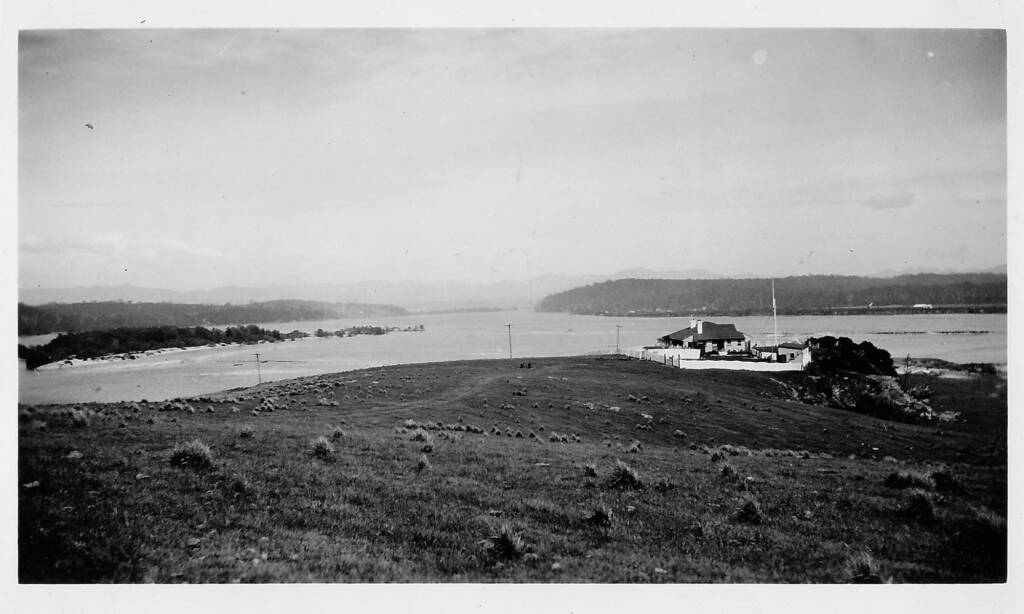

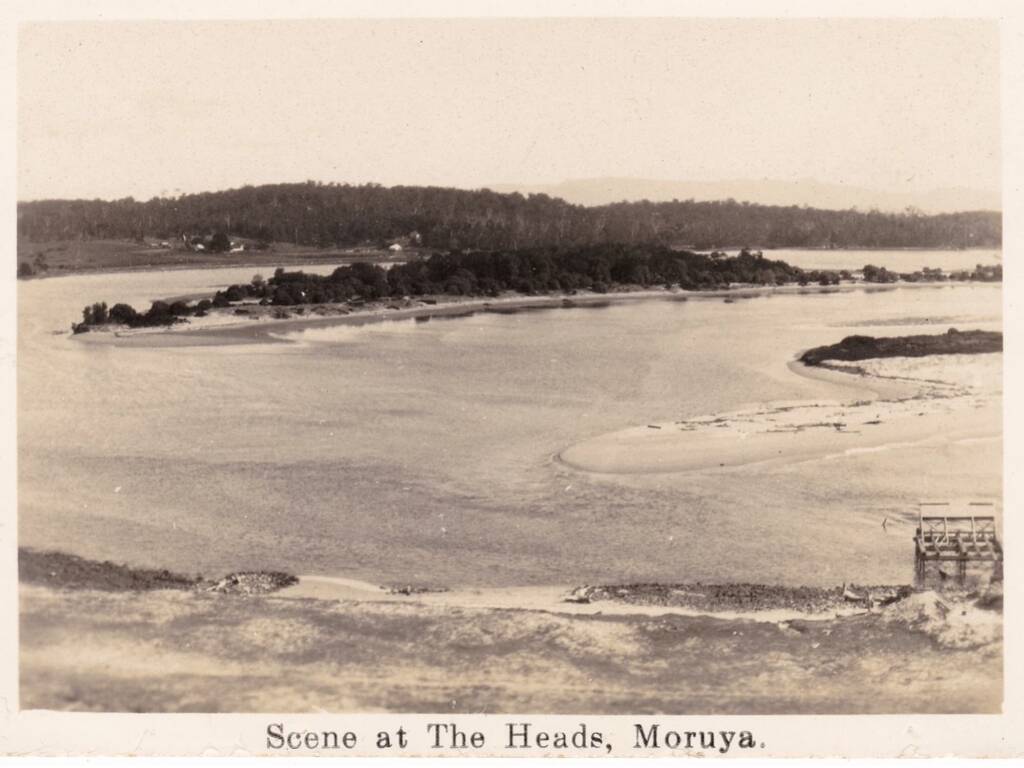

Fig 1 shows an area in southern New South Wales at Moruya Heads, dating back more than 80 years ago when the area had been used for cattle grazing. Trees had been cleared for the cattle, and mangroves had been removed from the Moruya River to allow the passage of boats to facilitate coastal shipping of goods. Grazing had further reduced the stability of the land around the water edge, leaving little vegetation and resulting in erosion.

Fig 2 shows the same area today, after South Heads Moruya and its surroundings had been returned to nature as part of the Eurobodalla National Park.

– showing part of the new nature reserve © Phil Warburton

Furthermore, beyond the National Park area, leafy urban gardens also replaced bare fields, and smaller urban reserves preserved some natural spaces. bringing back an environment that favoured a diversity of wildlife.

A rock barrier was placed in the Moruya River near Quandolo Island, to reduce erosion and mitigate flooding. A stand of mangroves was established that stabilised the land and which trapped silt and soil. Over an extended period, this has created suitable soil structures for a wider variety of plants and trees. After several decades, land has been restored to forest, where for years there were bare sandy shallows (Fig 3 and Fig 4).

This area around south Heads Moruya is now the northern part of the Eurobodalla National Park. The park stretches southwards from there, for 50 kilometres down to Mystery Bay. It takes in several urban developments but also forests, coastal lakes and estuaries that are critical breeding grounds for endangered shore birds. The park provides habitat for a wide variety of animals and plants.

The park contains extensive nature walks including the 14Km Bingi Bingi Dreaming track in an area of important cultural significance for First Nation people.

with Gulaga/Mount Dromedary in the background © Phil Warburton

There are several spectacular lookouts over the ocean, including a popular whale-watching vantage point at Dalmeny.

in southern NSW, Australia © Phil Warburton

So, in conclusion, whilst our natural ecosystems undoubtably face an uncertain future, the recovery of areas set aside for nature reserves shows that there is a pathway forward to protect some portions of our natural world.

The Eurobodalla National Park is now a valuable and stable ecosystem that is rich in plant and animal life.

Check out other blogs and content by Phil Warburton

Footnote & References

- Eurobodalla Biodiversity Strategy: https://www.esc.nsw.gov.au/council/major-projects/current-projects/planning-recreation-business/biodiversity-strategy

- More of Phil Warburton’s photographs of the Eurobodalla National Park can be found at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/philipnsw/albums/72177720315009293/