Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve is home to a cluster of 12 meteor craters, that were formed (some 4,700 years ago) when the Henbury Meteor, weighing several tonnes and accelerating to over 40,000 kilometres per hour, disintegrated before impact the earth.

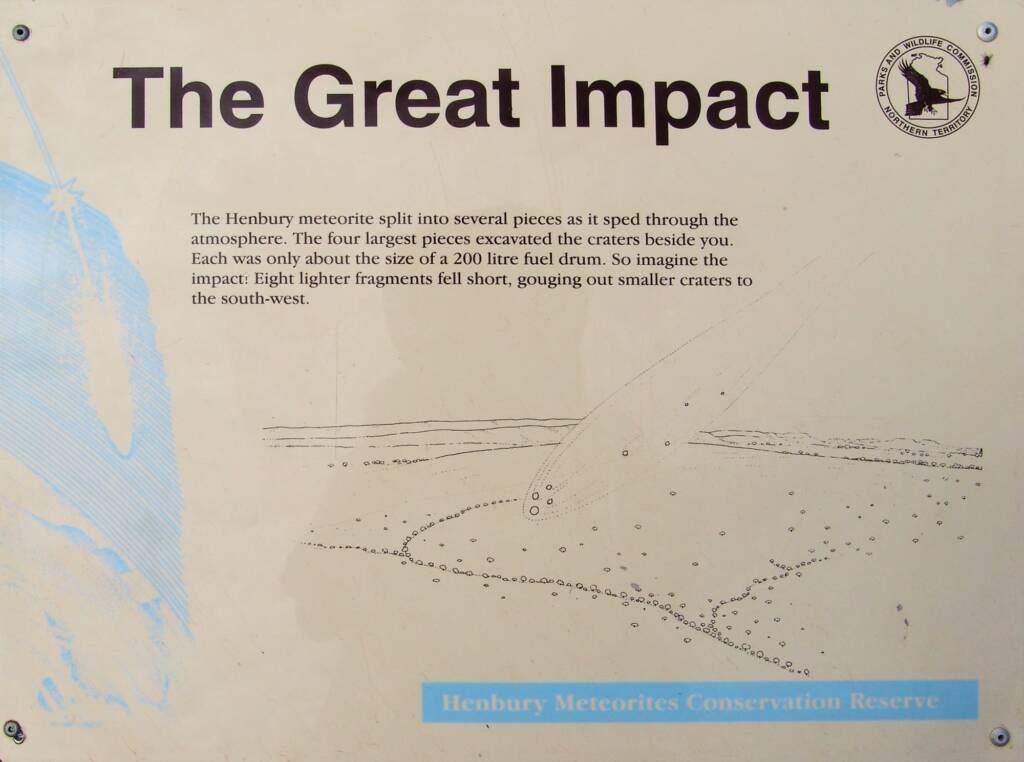

The Great Impact

Source: Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve (park signage), NT

The Henbury meteorite split into several pieces as it sped through the atmosphere. The four largest pieces excavated the craters beside you. Each was only about the size of a 200 litre fuel drum. So imagine the impact: Eight lighter fragments fell short, gouging out smaller craters to the south-west.

Located just 145 kilometres south-west of Alice Springs, off the Ernest Giles Road, the reserve provides for a self-guided walking track around the craters, the largest of which is 180 metres wide and 15 metres deep. The smallest of the crater is only 6 metres wide and a few centimetres deep.

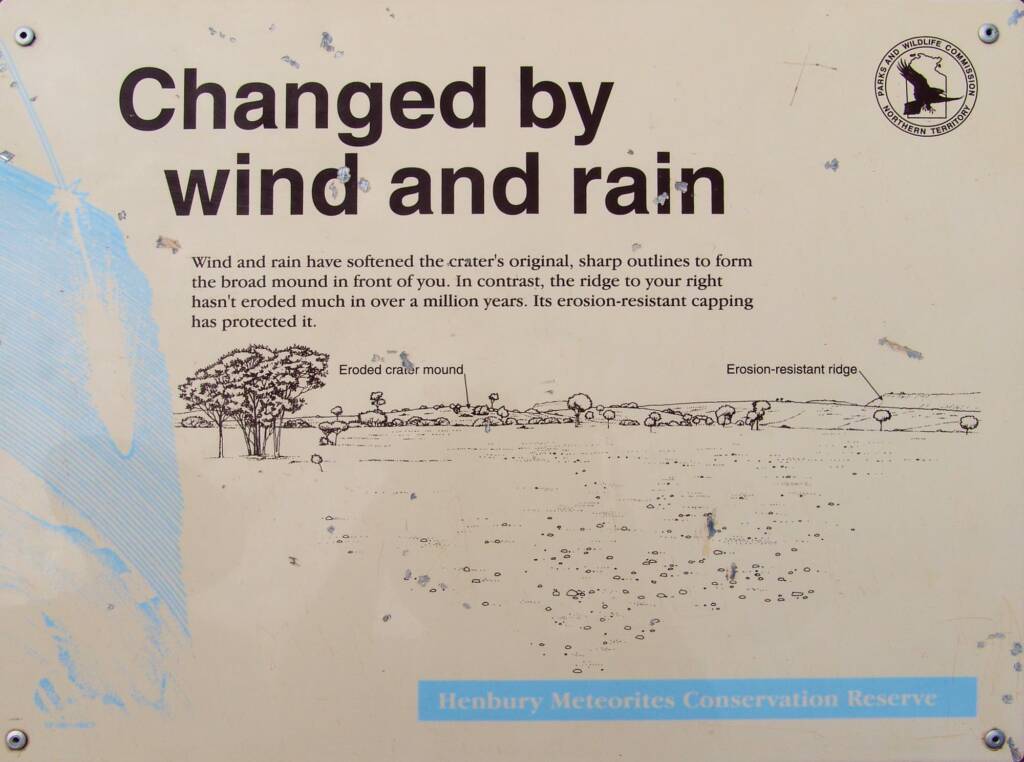

Time has eroded the sharp outline of the craters, but for the photographer, the best part of the day to visit is early morning or late afternoon, when the sun defines the craters more clearly.

Changed by wind and rain

Source: Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve (park signage), NT

Wind and rain have softened the crater’s original, sharp outlines to form the broad mound in front of you. In contrast, the ridge to your right hasn’t eroded much in over a million years. Its erosion-resistant capping has protected it.

The meteor fragments consisted mainly of iron (90%) and nickel (8%). Over 500 kilograms of the metals have been found on the site, with the largest being over 10 kilograms. Few specimens now exist in the area. Fragments of the meteor can be seen at the Museum of Central Australia in the Alice Springs Araluen Cultural Precinct.

Access

Located about 145 km south west of Alice Springs, about 118 km along the Stuart Highway, take the right hand turn onto a gravel road known as the Ernest Giles Road. This road leads to Watarrka National Park (Kings Canyon), part of which is a 4WD access road. You travel 8 km along the road and then take turn north for another 5 km to the Reserve’s entrance. The section of road to the Henbury Meteorites craters are accessible by 2WD vehicles, although there may be times due to weather conditions when the road becomes impassable.

Activities and Facilities

Picnicking, bushwalking and camping — there is picnic facilities at the camping ground and a pit toilet. There is no drinking water, and visitors should ensure they bring enough water. Firewood should be collected before entering the Reserve.

A Henbury fact sheet can be downloaded from the NT Parks and Wildlife site.1

Source: Parks and Wildlife Service of the Northern Territory, Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve

Flora and Fauna

The flora found in the craters interior and surrounds include Old Man Saltbush (Atriplex nummularia), Cassia, Eremophila, Ptilotus, mulga (such as Acacia aneura), whitewood (Atalaya hemiglauca), dead finish (Acacia tetragonophylla) and a variety of other Acacia species. In season there appears different species of daisy (such as everlasting), wild hops, and a variety of tough grasses.

Fauna include reptiles such as Long-nosed dragons, Central netted dragon, and the occasional larger goannas; birds such as budgerigars, finches, silvertails, ravens and birds of prey. Larger animals include cattle, wild horses, kangaroos and dingoes, may sometimes be seen.

Of course for those interested in Entomology (insects) and arachnids, there is certainly plenty to see if you look closely. As well as flies (and who doesn’t know about them, although there are many different species), there are also butterflies, moths and wasps. If there is water around, you will see the mud wasps including the larger potter wasp (Delta latreillei) and the similar Abispa ephippium. There are various Arachnida including spider species and scorpions.

Also keep your eyes open for our native bee species, especially when the plants are in flower. Some of our native bee will nest in the ground, whilst others (such as the male of the species) will roost on plant stems and twigs of trees and shrubs. Whilst you don’t see them every year, cicadas can be heard from their loud songs.

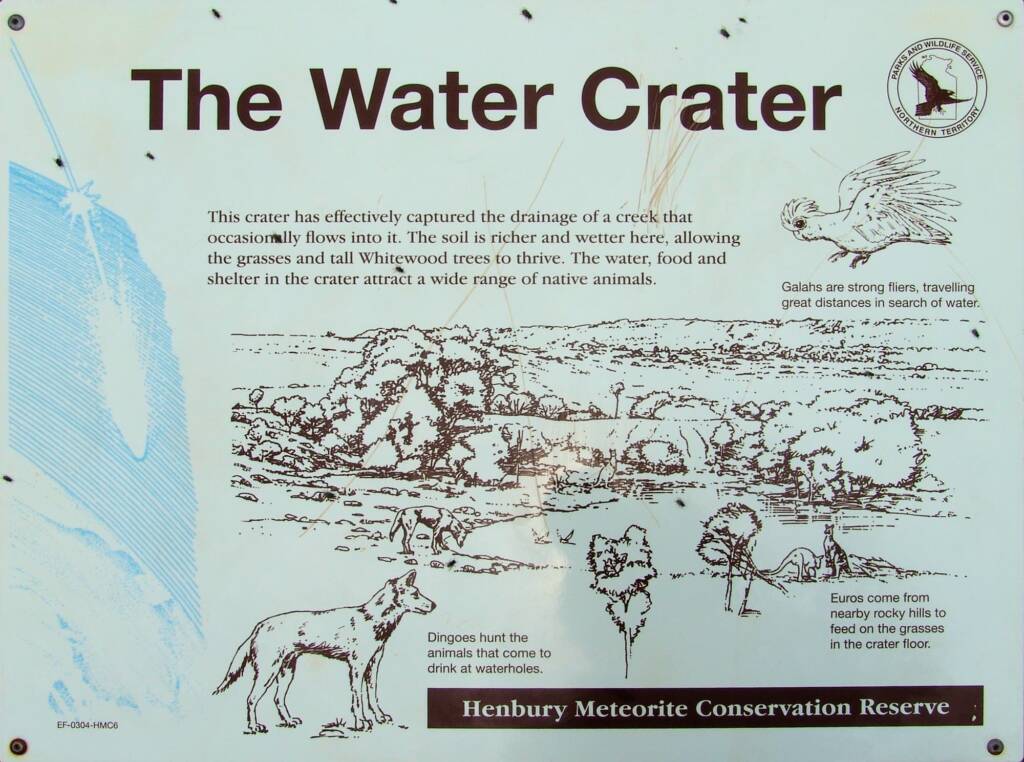

The Water Crater

Source: Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve (park signage), NT

This crater has effectively captured the drainage of a creek that occassionally flow into it. The soil is richer and wetter here, allowing the grasses and tall Whitewood trees to thrive. The water, food and shelter in the crater attract a wide range of native animals.

Galahs are strong fliers, travelling great distances in search of water.

Euros come from nearby rock hills to feed on the grasses in the crater floor.

Dingoes hunt the animals that come to drink at waterholes.

Where did the name Henbury come from

The craters are named after Henbury Station, a nearby cattle station. The cattle station was was named in 1875 after the family home of the founders from Henbury in Dorset, England. Exploring the vast cattle station in 1899, Walter Parke came upon a feature in the landscape he could not explain. It was a 15 metre deep, bowl-shaped depression, which was larger than a football field, that was gouged out of the Central Australian desert.

“One of the most curious spots I have ever seen in the country,” he wrote in a letter to the anthropologist Frank Gillen. “An immense amphitheatre…To look at it I cannot but think it has been done by human agency, but when or why, goodness knows.” 2

It wasn’t until the Karoonda meteorite that fell on South Australia in 1930, that interest was shown for the craters at Henbury. The first scientific investigations of the site were conducted by A.R. Alderman of the University of Adelaide, with his result published in a 1933 paper entitled The Meteorite Craters at Henbury Central Australia, with numerous other studies being undertaken.3 4

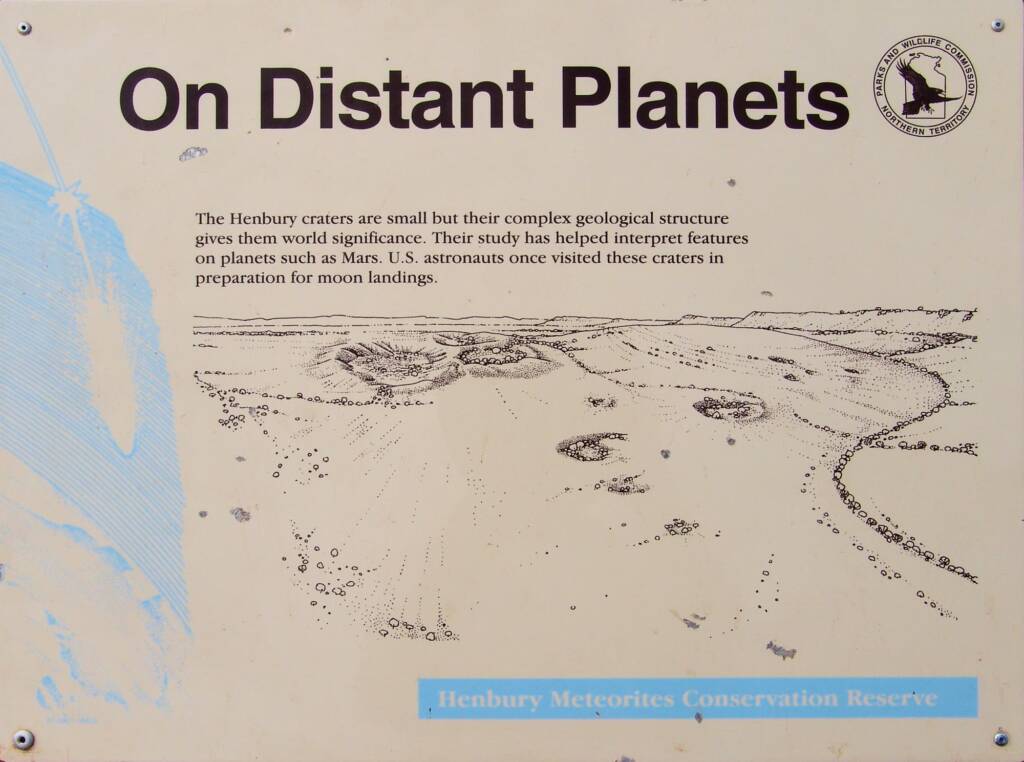

On Distant Planets

Source: Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve (park signage), NT

The Henbury craters are small but their complex geological structure gives them world significance. Their study has helped interpret features on planets such as Mars. U.S. astronauts once visited these craters in preparation for moon landings.

Cultural Significance

The Henbury crater field lies at the crossroads of several Aboriginal language groups, including Arrernte, Luritja, Pitjantjatjarra, and Yankunytjatjara. It is considered a sacred site to the Arrernte people and would have formed during human habitation of the area.5

Local prospector, J. M. Mitchell6, said that older Aboriginal people would not camp within a couple of miles of the Henbury craters. An elder Aboriginal man who accompanied Mitchell to the site explained that Aboriginal people would not drink rainwater that collected in the craters, fearing the “fire-devil” would fill them with a piece of iron. The man claimed his paternal grandfather had seen the fire-devil and that he came from the Sun. An Aboriginal contact said of the crater field: tjintu waru tjinka yapu tjinka kurdaitcha kuka, which roughly translates in the Luritja language as “A fiery devil ran down from the Sun and made his home in the Earth. He will burn and eat any bad blackfellows.” This indicates a living memory of the event.7

Charles Mountford8 (an Australian anthropologist and photographer) recorded that the largest of the crater formation was attributed to anthropomorphic lizard woman (called Mulumura), tossing soil out of the crater, forming the crater’s bowl-shape. The soil discarded by Mulumura explained the piles of meteoritic iron around the craters and the presence of ejecta rays (which are unique to terrestrial impacts but are now gone due to prospecting at the site).9

The Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory give the Arrernte name for the crater field as Tatyeye Kepmwere (or Tatjakapara) and whilst “some of the mythologies for the area are known, they will only be used for interpretation purposes after agreement by the Aboriginal custodians of the site.”

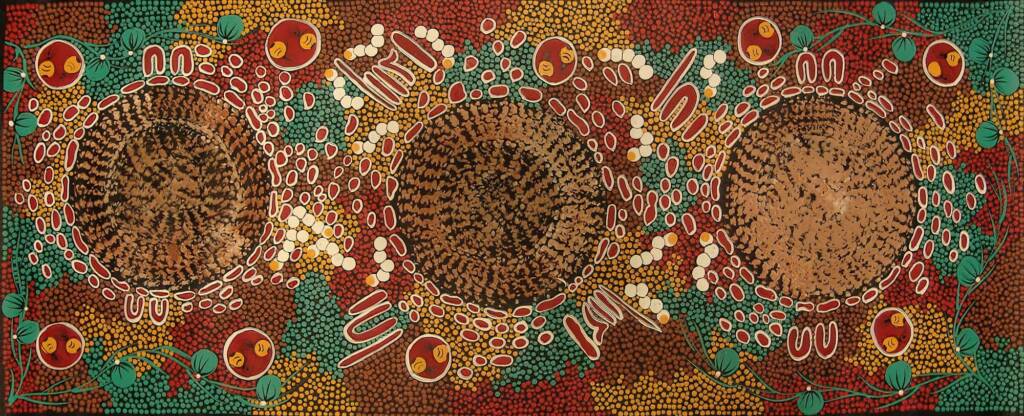

Aboriginal Astronomy

Aboriginal culture is steeped in astronomy, used by the indigenous Australians in practical ways, as with navigating the land and defining seasons and the natural world around them. They were part of their “dreaming stories”, passed down through the generations. In the oral traditions, they covered astronomical activities and events such as meteors. Often the appearance of meteors were associated with evil magic, omens of death and punishment for the breaking of laws and traditions. There is one story of a meteor as the bringer of life.

The Luritja artist Trephina Sultan Thanguwa tells such a story in her painting Kulu, about a meteor having landed on the earth and spliting three ways…

All the animal’s had a big meeting.

Who was going to carry the egg of life up to the universe. The Kulu was chosen.

When you see where the egg of life was carried

Meteorite has landed and dropped, split three ways.

This is our memory of the Kulu

And life began.

Footnote & References

- Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve, Parks and reserves, NT Government, https://nt.gov.au/parks/find-a-park/henbury-meteorites-conservation-reserve

- Meteorite craters in Australia, by Beau Gamble, 1 August 2012, Australian Geographic, https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/science-environment/2012/08/meteorite-craters-in-australia/

- Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henbury_Meteorites_Conservation_Reserve (last visited June 17, 2022).

- Alderman, A.R. (1931). The meteorite craters at Henbury, Central Australia with an addendum by L.J. Spencer, “Mineralogical Magazine”, Volume 23, pp. 19-32.

- Hamacher, D.W. and Norris, R.P (2009). Australian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts? Archaeoastronomy: the Journal of Astronomy and Culture, Volume 22, pp. 62-95. Bibcode:2009Arch…22…62H

- Mitchell, J.M. (1934). Meteorite Craters – Old Prospector’s Experiences. The Advertiser, Adelaide, South Australia, Thursday, 11 January 1934, p. 12.

- Hamacher, D.W. and Goldsmith, J. (2013). Aboriginal Oral Traditions of Australian Impact Craters. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Volume 16(3), pp. 295-311

- Mountford, C.P. (1976). Nomads of the Australian Desert. Rigby, Ltd., Adelaide, pp. 259-260.

- Buhl, S.; McColl, D. (2012). Henbury Craters and Meteorites: Their Discovery, History, and Study. Springer Press.

- Impact Craters in Aboriginal Dreamings, Part 1: Henbury by Duane Hamacher, Australian Indigenous Astronomy, http://aboriginalastronomy.blogspot.com/2011/03/impact-craters-in-aboriginal-dreamings.html

- Trephina Sultan Thanguwa, https://ausemade.com.au/art-culture/aboriginal-artists/trephina-sultan-thanguwa/

- Henbury Craters, Mars Society Australia (MSA), https://marssociety.org.au/project/geology/place/henbury-craters

Northern TerritoryCentral Australia Aileron Alice Springs Binns Track Chambers Pillar Historical Reserve Ernest Giles Road Finke Gorge National Park Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve Hermannsburg Historic Precinct Ilparpa Claypans Karlu Karlu / Devils Marbles Conservation Reserve MacDonnell Ranges Mount Connor Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary Owen Springs Reserve Red Centre Way Drive Standley Chasm Tnorala (Gosse Bluff) Conservation Reserve Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Watarrka National Park & Kings Canyon Wurre / Rainbow Valley