Dragonfly or Damselfly?Side by Side The Little and Large Show The Shell Game Going to Extremes Side by Side answer Going Zen The Rule Acknowledgement of sources

Author Jeff Melvaine ◦

The Rule: Is there a simple “dragonfly or damselfly” rule for Australian Odonates?

Let’s redo that table of differences, taking into account the exceptions and additions noted above. * denotes that there are exceptions for some non-Australian species; complications relating to damsel dragons are not marked, to reduce clutter.

| Characteristic | Dragonfly | Damselfly |

|---|---|---|

| Discoidal cell in each wing | Triangle, occasionally irregular, + hypertriangle | Quadrilateral, rarely open at base |

| Male tail claspers | Two cerci (upper), one epiproct (lower) * | Two cerci (upper), two paraprocts (lower) |

| Male grip on female | At the top of the head * | At the top of the first thoracic segment |

| Wing posture when perched | Almost always open, very few exceptions | Usually closed, significant exceptions |

| Eye placement | At front of head | At side of head |

| Eye separation (front-on view) | Eye separation (front-on view) | More than the width of one eye |

| Build | Usually robust | Usually slender |

| Size | Mostly medium to large, rarely tiny to small | Mostly small to medium large, rarely large * |

| Fore and hind wing structures | Very rarely similar | Nearly identical * |

| Wing stalks | Extremely short | Always long * |

| Flight | Typically fast, persevering, agile | Typically slow, intermittent, but also agile |

| Larval tail lobes | No | Yes, variously specialized, sometimes as gills |

| Larval rectal gills | Yes, enhanced by strong muscular pumping action | Yes, but no pumping action |

So the rule (for Australian species) could be formulated as follows:

If you have a sufficiently detailed view of the wing venation, then check the discoidal cell; a triangle (possibly lacking some sharp corners) + hypertriangle indicates a dragonfly, a quadrilateral (possibly open at the wing base) indicates a damselfly. Sometimes the easiest part of the wings to see is the base. If this is a long narrow stalk, that identifies a damselfly; if it widens abruptly close to the base, that identifies a dragonfly. But for Odonates in flight, unless gliding very passively, the wings are likely to be just a blur.

If you have a sufficiently detailed view of the tail claspers of a male, one lower appendage indicates a dragonfly, two completely separate lower appendages indicate a damselfly.

If you manage to find a highly visible pair, then check where the male is gripping the female with his tail claspers: on the head indicates a dragonfly pair, on the first segment of the thorax indicates a damselfly pair.

What about the other 90% + of the time? The most reliable indicator is the spacing between the eyes at the point of closest approach to each other, which is often at the top of the head. If this spacing is less than the width of one eye, measured from the front-on facial view, it’s a dragonfly, otherwise it’s a damselfly.

If you have a side-on view of a perched individual, then you will probably have a view of the overall wing shapes. The most easily observed feature for a damselfly is that each wing has a narrow stalk at the base. For a dragonfly, the wings widen much more suddenly, and the hindwing widens at least somewhat more than the forewing, usually much more so. This feature does not require squinting at fine detail on the level of the individual wing veins.

A rule for world Odonata would be rather more complex. It would need to separate the damsel dragons too, at least for observers in the restricted habitats that Epiophlebia occupies.

The above is about as concise as I can make it, so rather than trying to summarise, examples of how to apply the rule to photos of some more species may help. Here is a quartet of male Palemouths (Brachydiplax denticauda) in earnest contention for the best breeding sites at a small lagoon in Kyogle, NSW.

Detail in this view is highly compressed and mostly difficult or impossible to resolve, but one detail does stand out; the top left male has eyes that meet along the midline of the head. That makes it very clear that the species is a dragonfly.

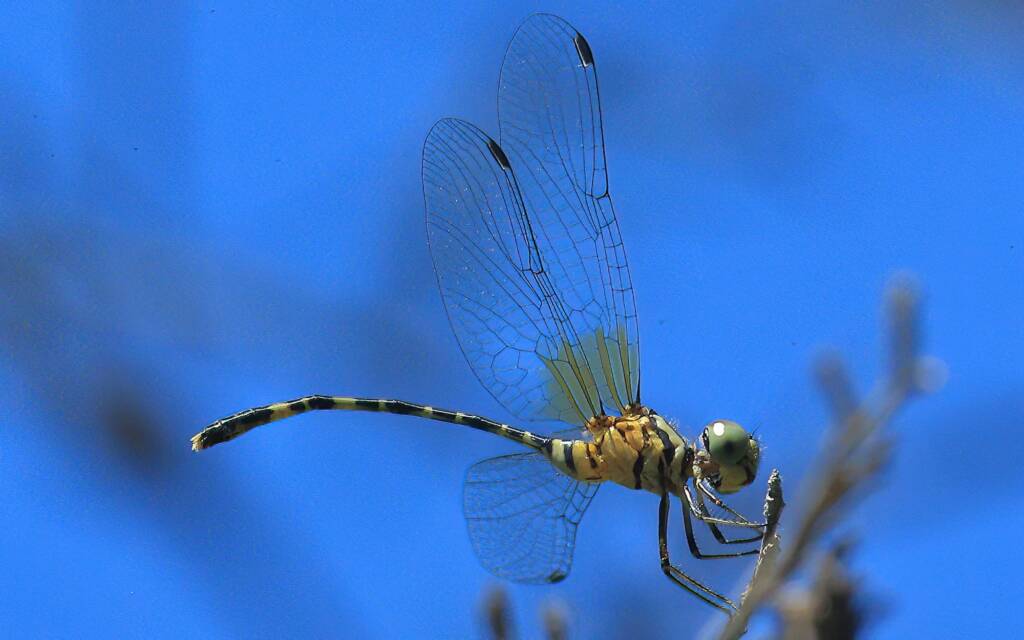

Now look at this male Australian Emerald (Hemicordulia australiae), hovering with wings in energetic motion at Karawatha Forest, Queensland.

Again, many of the defining characters that separate dragonflies and damselflies are obscure in photos like this. But here too, the meeting of the eyes along the midline of the head is decisive: dragonfly.

What about this male Australian Tiger (Ictinogomphus australis) at Billabong Sanctuary in North Queensland, gliding with wings almost perfectly still? A surprising amount of detail is visible here.

It shows the discoidal cells in the right wings with clearly defined triangles characteristic of dragonflies. On a broader scale of detail, the wing shapes also proclaim dragonfly emphatically; the hind wings in particular expand to almost maximum width very close to the base. The separation of the eyes is harder to judge from behind, but they must be at least very close to the midline. (In fact, they do not actually meet.)

Sometimes the photographer gets lucky and captures a lot of detail from a near-perfect angle with a sympathetically light-toned background. This is much more easily achieved with perched subjects, like this Red Arrow (Rhodothemis lieftincki) at the storm drains in Tweed Heads South. NSW.

Here we see typical pond dragonfly wings, with a deep base to the hind wing that fits snugly against the body. The discoidal cells contain clearly defined triangles. The view of the eyes is less direct, but it is clear that they come close together. (In fact, they do meet at the very top, but it takes a favourable angle to show this.)

A slightly trickier proposition is this female Unicorn Hunter (Austrogomphus cornutus) from Tenterfield Creek NSW.

Here the wings are in the closed but somewhat raised position adopted by some damselflies; we have seen this before with another clubtail, the Stout Vicetail (Hemigomphus heteroclytus). The pale colour hints that this might be a teneral that has recently moved away from the larval shell, and the narrow eye spacing confirms that this is actually a dragonfly. The broad base of the hind wings is consistent with this conclusion, and cryptic hints of triangular discoidal cells can be seen in this cluttered view of the wing venation.

A rather better view of the wing venation is offered in this next example, a young female Common Archtail (Nannophlebia risi) from the Rocky (Timbarra) River In northern NSW.

This view shows a feature of some of the smaller pond dragonflies in the family Libellulidae: the discoidal cells feature what looks like a triangle clipped at some of the corners. It’s a small and somewhat frail-looking species that, like typical damselflies, asserts its breeding territory from a perch, although, like the Rockmaster damselflies, it will defend that territory actively. At nearby Demon Creek I saw a male dart out from his perch to challenge an intruder; the two of them rose face to face in a rapid spiral (too fast for my camera) for about two metres, until one began to feel the pressure, and turned and fled out of sight. The most direct confirmation that this is a dragonfly is in the broad base of the hindwing and the absence of narrow basal stalks; the eyes are certainly large, but the degree of their separation (they actually meet across the midline of the head) is conjectural from this view.

Next we have a Bronze Needle (Synlestes weyersii) male posing under highly favourable conditions for photography on the banks of the Ebor River, near the pub at Ebor, NSW.

This is instantly recognisable as a damselfly from three features: wide eye separation with placement at the sides of the head, long narrow wing stalks, and long thin quadrilateral discoidal cells. The wings are not always so widely spread in this genus, but are not often seen closed.

Next, a Giant Rockmaster (Diphlebia hybridoides) male from Mount Lewis, Queensland, also looking a little odd.

What’s odd here is that it has mature colour and is perching with closed wings like a teneral; no other individual that I found in the area did that. As in the case of the Arrowhead Rockmaster that we met previously, an open-winged posture is expected of mature individuals. So there is logic, and there is acceptance of the need to expect the unexpected at times. The wing shape is unequivocally that of a damselfly, with long narrow stalks at the base, and the eyes appear in this oblique view to be well separated and positioned at the side of the head.

Finally, a Dusky Spreadwing (Lestes concinnus) male, from Port Douglas, Queensland.

This is that other damselfly genus with one Australian member that holds the wings open when perched. The image is too noisy to convey the wing venation very clearly, and significant parts of the discoidal cells are almost impossible to make out. However the wing shape with long narrow basal stalks is conclusive, as is the eye separation; this is a damselfly.

What is the theme here?

Or, more specifically, why did I bother to plough through all this detail? Few of the readers here would need this information the way a professional entomologist would, although some might feel curious about terminology that seems to contradict the usual rules of thumb.

The basic theme is central to all biology; survival requires the ability to adapt to change, and exploit new opportunities. The more species you look at, the more diversity of survival strategies you encounter. This rather complicates the process of classification; the path to survival can wind around in many dimensions, and similar-looking solutions can develop from very different starting points.

Dragonfly or Damselfly?Side by Side The Little and Large Show The Shell Game Going to Extremes Side by Side answer Going Zen The Rule Acknowledgement of sources

Footnote & References

- Author Jeff Melvaine / Photographs © Jeff Melvaine

Dragonflies & DamselfliesDragonfly or Damselfly? Sex Lives and Dragonflies Damselflies Diplacodes haematodes Hemicordulia tau Orthetrum caledonicum Orthetrum migratum Orthetrum villosovittatum

InsectsBees Beetles Blattodea Butterflies Coleoptera Cicada Crabronidae Diptera Dragonflies & Damselflies Formicidae Hemiptera Heteroptera (True Bugs) Mango Planthopper Moths Orthoptera Orthopteroid Processionary Caterpillar Stink Bugs, Shield Bugs and Allies Syrphidae Wasps Water Scorpion (Laccotrephes tristis) Witchetty Grub